We took the long way around to get back where we started. How can you make what is essentially 2-6 hours of a talking head something people will want to watch?

In the previous installment our dialogue focused on how to take a video deposition with a mind to how it would be used in a subsequent hearing or trial. Like anything in life, if you want the best final product, start with the best materials. That, however, is not always something you can control. Your most important witnesses are generally called for deposition by the opposition.

Your preparation and training of the witness will have some effect on what you have to work with in preparing for trial, but the attorney across the table did not ask questions to help you win.

While you have taken the best deposition possible, unless you were the only questioner, you were not left with a deposition ready for prime time. We’ll now look at how to take what you have and turn it into what you want.

What is the story?

In a recent case we defended, our co-counsel took the deposition of an unhappy former employee. The witness was called to support our position. The witness had no preparation and co-counsel wasn’t familiar with her or what she knew. After the deposition he reported that her appearance, her demeanor, and her answers didn’t come across well. Because of that assessment, on initial review it looked like we had little we could use. She was listed as a witness, but we had only prepared a very limited presentation.

As the case developed it became clear that much of what she had said would be useful. We needed to use the deposition in spite of the lack of makeup, flyaway hair and coarse language. Initially the clips were chosen based on anything that could be useful, without regard to admissibility, demeanor, or clarity. With about 2 hours of material we started to cull, first for admissibility, then for clarity.

After several re-edits, and the court’s rulings, we ended up with about 35 minutes that fully supported our position and gave precious little to the opposition, even though their designations were included and fully a third of the clips came from their cross examination.

When we polled the jury after their verdict, we asked what they thought of our witness. One juror said she was one of the most believable witnesses even though she seemed a little rough, but “everyone in Texas has a friend or a cousin or an in-law just like her.”

How long is a story?

Like it or not we live in a society with a decreasing attention span. An interesting documentary usually lasts 40 to 50 minutes. That is about how long those in the know think they can keep your attention. Dull documentaries are about the same length, they just seem longer. That translates to about 35 pages of transcript. One page (Twenty five lines) generally takes 1.25 to 1.5 minutes.

Before the deposition starts, the court should be informed of how long the deposition will play. If your deposition lasts longer than about 40 minutes, you might want to ask the Judge if you can take a break about ¾ of the way through.. In some courts, federal courts in particular who tend to run a tighter ship, the length of a video deposition will be tightly controlled and you need to be prepared for that.

Is that all the story?

The party calling the witness should, in most cases, play the designations from both sides. If each side plays their portions separately the fact finder is left to try to piece together related information presented severally. Both parties want their side of the story told, but since they are pulling from the same material it can’t be done without repetition. The Rashomon Effect is often used effectively in movies. That is where the same events are described from different perspectives, leaving the viewer to decide what they want to believe. It doesn’t work so well with depositions.

Please look at the exhibit

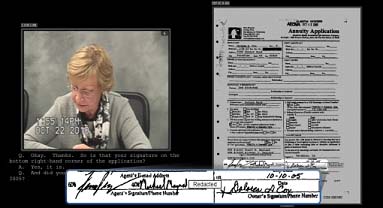

In Digest #1 talking about effective slideshows, we introduced the concept of the “focus shift”. Changing the image on the screen forces the viewer to re-focus their attention. While taking the deposition, there can be subtle reframing, but the witness is still the primary focus.

Most trial presentation programs will allow you to put the recording in a corner and bring up the document. This shifts focus. The relevant section or paragraph can be blown out, and the salient words can be highlighted. When discussion of the document is finished the witness again fills the screen, providing another focus shift.

He said what??

Another ability of presentation programs is to have closed caption, simultaneously displaying the text while the deposition plays. This can be useful, particularly if the deponent is difficult to understand or the quality of the audio recording is poor. It is also very helpful if any of the finders of fact have a hearing disability. On most programs closed captioning can be toggled on or off.

We previously discussed the “redundancy effect” and the “split attention effect”. Those effects address diminished retention caused by receiving redundant oral and visual signals simultaneously and having to split attention between multiple information inputs.

Scrolling text is not always the best choice. Have you ever watched a closed captioned program, or a foreign film with the translations on screen? It is a natural tendency to focus on the scrolling text. One of the strengths of a visual record is to watch the demeanor of the witness. The viewer will miss most of that if they are reading the transcript.

What is she talking about?

We are all familiar with how a deposition works. It is not uncommon to start on a topic, exhaust what you understand, then later when more information comes out, return to that topic. It is again touched upon in cross or redirect. In editing the deposition sequentially, the discussion is disjointed.

It is also not unusual to have to address events out of chronological order. Sequential editing can make you story sound like “this happened, then this, but before that something else happened, then the other stuff, and after that it ended up here.”

In the interest of clarity or to assist the fact finder in understanding the evidence, a deposition can, with court approval, be edited by topic or by chronology. A complete discussion of this methodology can be found in Gregory Joseph’s Modern Visual Evidence § 3.03[2] [iii]- Integrated-Edited Video Recordings citing Fed. R. Evid. 611(a), Beard v. Mitchell, 604 F.2d 485, 503(7th Cir. 1979), Federal Judicial Center’s Manual for Complex Litigation Fourth § 22.333 (2004) among others.

What are they looking at?

Ideally the video is playing on a single screen, large enough and positioned so everyone on the jury has a clear view. When displaying with projector, use one bright enough that the lights don’t need to be dimmed. Many courtrooms today have the audio/video electronics installed. Not all of them have done it well. Some courts have small screens for the jurors. This is less than ideal for video depositions. When all the fact finders are focused on the same object there is a positive effect on concentration. It also makes it easier to tell who is asleep.

Did you catch that?

We all know the drill. Tell them what you’ll tell them, tell them, and remind them that you told them. This can be especially important with video testimony. Even with all the methods to not make it so, fact finders often pay less attention to video than to a live witness. In opening, you can introduce your witness with a screen shot from the video, explaining the important points to which they will testify. In closing, use the screen shot again pointing out where their testimony fits your client’s theme and story.

At R-D Consultants we have prepared and edited thousands of depositions. We have been instrumental in providing counsel feedback and suggestions toward making those depositions more effective in the courtroom. We look forward to working with you to that end.

Contact

Ric Dexter

R-D Consulting at ric@rdexter.com

or visit our web page at rdexter.com